After leaving I-40 we wound our way along the Foothills Parkway, a crooked, two-lane roadway through heavily wooded mountainous terrain. The quiet beauty calmed us after the nerve-wracking drive crushed between semi’s and the concrete wall dividing the interstate as it snaked its way over the mountains. Our destination awaited only a few miles away in Gatlinburg. We soon reached the congested streets of the vacation mecca atop the mountains. Turning left, we climbed, passing motels and restaurants, until we reached the narrow, steep, winding driveway up to the top where our hotel, the Park Vista, stood overlooking the narrow valley that is Gatlinburg.

This was where the 276th Armored Field Artillery chose to hold their final reunion. The destination for five aging WWII veterans to reunite once more. Time may have reduced their numbers but not their spirits. The dwindling group of veterans and their families were joined by sons, daughters and wives of other, already deceased veterans – all coming together to remember and celebrate their service so many years ago.

My husband was one of those sons of deceased 276th veterans. We were newcomers to the reunions yet we were welcomed into the fold like long-lost relatives. The people who gathered at the Park Vista, related only by the service of a group of young men almost seventy years ago, were the most gracious, most friendly and warmest group of people we have ever encountered.

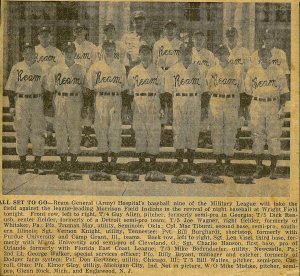

Organized in 1943, the 276th AFA Battalion was one of several artillery units converted to mobile, track-mounted 105 mm Howitzers (M-7’s) to provide mobile artillery support to infantry and armored divisions. In the summer of 1944, after the D-Day invasion at Normandy, the 276th crossed the Atlantic, landed in England, then crossed the channel to France. The Battalion fired its first combat round in September, 1944. From that point they were in continuous combat, battling their way across Europe, until the Germans surrendered in May, 1945. By July, they were again crossing the Atlantic, but this time their destination was home, not for good, but for additional training before being sent to the Pacific. The war with Japan still raged. Fortunately for these combat weary young men, the Japanese surrendered before their unit was redeployed.

The veterans of the 276th fascinated us with their positive, even joyful, attitudes as they answered questions, re-told old stories and remembered their fellow soldiers who had passed away in the intervening years. Sons and daughters shared stories their fathers had told to them. None of the five were officers. Their military jobs ranged from clerk to radio man to mechanic to driver yet they told stories of bullets that came within inches, artillery shells bursting nearby, encounters with enemy soldiers and freezing weather.

Of the five Batteries in the Battalion, four were represented at the reunion – Headquarters Battery, Battery A, Battery C, and Service Battery. Pictures of earlier reunions, with the participants all decked out in their finery, relayed the history of these events. A map detailed the Battalion’s journey as it fought its way across France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany and Czechoslovakia. Old pictures were perused for familiar faces. Watching a taped interview with one veteran brought a lump to my throat and tears to my eyes. Such amazing men who went off to war at such a young age leaving their families and loved ones behind.

They journeyed from various locales to reunite with old friends. For these elderly men and their wives the trip could not have been easy nor possible without help from their families. The devoted son of one veteran organized the event and, despite his father’s failing health, drove from Indiana so there could be one last reunion. The eldest veteran, at ninety-seven, flew in from Massachusetts accompanied by his daughter and son-in-law. Another man from Georgia brought his wife, children, grand-children and great-grandchildren. And a former Tennessean and his wife were transported from Cincinnati by their son and daughter-in-law.

They journeyed from various locales to reunite with old friends. For these elderly men and their wives the trip could not have been easy nor possible without help from their families. The devoted son of one veteran organized the event and, despite his father’s failing health, drove from Indiana so there could be one last reunion. The eldest veteran, at ninety-seven, flew in from Massachusetts accompanied by his daughter and son-in-law. Another man from Georgia brought his wife, children, grand-children and great-grandchildren. And a former Tennessean and his wife were transported from Cincinnati by their son and daughter-in-law.

The son of a deceased veteran drove down from Milwaukee. This faithful son told of his trip to Europe to retrace the route of the 276th. He and his father, both devoted history buffs, had attended previous reunions and the son had known many of the 276th veterans. They planned to take the European trip together but his father did not live to make it so the son went alone in honor of his father.

Another son, daughter and son-in-law journeyed across the mountains from North Carolina for the reunion. Like my husband’s father, their father never came to any of the reunions. He talked of his service but would never contact any of the men he served with. After his death his son decided to meet some of the men his father fought with so many years ago and participate in the reunions. Knowledgable and friendly, these North Carolinians shared stories from former reunions, of other veterans now gone and reenactments. They generously shared their photos, too.

The reunion was a special time for the aging men to reconnect and remember their youth. As Tom Brokaw said of the WWII veterans in his book “The Greatest Generation,” these men did not brag about their service. They quietly spoke of events but always expressed that they were just doing their job, doing what they had been trained to do, doing what they had to do. It was touching to watch them talk, and laugh and reminisce about those times.

In their young, formative years these men forged a bond like no other – the bond of combat. And they became our heroes. By doing their jobs, they enabled us, their children and grandchildren, to live the lives in a free, democratic society. They freed the world from the tyranny and dictatorship that threatened to engulf the globe. We so often forget that in 1943 when these young men first came together, the Allies were losing the war and it looked like it would take many years of fighting to defeat Germany and Japan. They had a big job ahead of them but they knew they would win – eventually. That faith in themselves, in this country, was remarkable. And we saw that same positive attitude in the remaining veterans that we met in Gatlinburg.

Too soon it was time to leave. Each of us going back to our own part of American. I hope we can stay in touch with these wonderful people, each fascinating in their own way. As we drove down out of the mountains and south toward Florida, we agreed that it had been a wonderful experience, a chance to touch the past, to talk with those who had lived it. Too soon they will all be gone, but they will never be forgotten.

![b17_flying_fortress[1]](https://barbarawhitaker.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/b17_flying_fortress1.jpg?w=300&h=196)

![b24liberator[1]](https://barbarawhitaker.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/b24liberator1.jpg?w=300&h=221)

![jimmy_LIFE_cover1945[1]](https://barbarawhitaker.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/jimmy_life_cover194511.jpg?w=225&h=300)