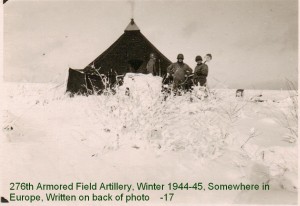

When we last left our hero’s of the 276th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, it was February, 1945, and they had just crossed into Germany from Luxembourg.

I’m a map person. Several years ago I purchased a coffee-table book “US Army Atlas of the European Theater in World War II.” Researching this post I scoured the maps for locations mentioned in the 276th Battalion history and that exercise put some of the distances in perspective. In a straight line from Bastogne, Luxembourg, to Bitburg, Germany, it’s about 30 miles through hilly, heavily wooded terrain with crooked, narrow roads. The defenses of the Siegfried line ran along the German border between the two points. Bitter cold winter weather hindered progress as the Germans retreated behind their “west wall” line of defense. Can you imagine life for the men? Living outdoors, eating when they could, following orders, doing their jobs, fearing the next attack and struggling to survive. The 276th was a few miles southeast of Bastogne at the beginning of January. They did not reach Bitburg until Feb. 28, 1945. Eight long weeks.

From the southern shoulder of the “bulge” in the line, due to the German counter-offensive later known as the Battle of the Bulge, the 276th moved toward the northeast in support of the 80th Infantry Division. On Feb. 7, 1945, the Battalion fired 1,702 rounds in preparation for the 80th attack across the Our River into Germany and against the Siegfried Line. The 276th fired a total of 2,610 rounds that day, more than 325 rounds per gun. After that firing continued at a rate of approximately 1,000 rounds per day as they continued to pound the German fortifications. On Feb. 19-20 the 276th again fired heavily in preparation for another attack by the 80th Division. This time the 276th AFA Battalion crossed the Sauer river into Germany near Cruchten.

During these attacks the 276th for the first time fired a mixture of rounds that consisted of 40% fuze delay, 50% fuze quick and 10% white phosphorus, a chemical that burned through anything and could not be extinguished with water. The combination proved effective against enemy troops and would be used again.

In early March they moved rapidly northward to Koblenz on the Rhine. My father-in-law told of sitting on high ground overlooking the Rhine river and seeing the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, north of Koblenz. Although not mentioned in the history, he remembered seeing the bridge and firing across the river to protect the crossing troops. Since it was the only bridge left intact across the Rhine, it had to be the bridge at Remagen. For years he had a print of the bridge hanging in his room.

His buddy in the 276th told a funny story on him years later. While near the Rhine, a young man, drunk on liberated cognac, sat astride the gun barrel when German artillery began firing rockets on their position. He couldn’t get down so he rode out the barrage on the tube. Shells landed so close that the water cans hanging on the gun were shot off, but he didn’t get a scratch. According to my husband, his father didn’t want the story told and tried his best to stop his buddy from telling it in front of his sons.

At Koblenz the north-east flowing Moselle joins the Rhine. On March 15 the 276th crossed the Moselle with elements of the 4th Armored Division. They continued toward the south-east against stubborn resistance from rear-guard troops and defiant towns. Although the men rarely knew what was going on overall in the war, they knew moving forward meant they were winning and that was always good news.

While the 4th Armored Division diverted south to take Worms, the 276th remained at Oppenheim to support a bridgehead operation by the 5th Division. They crossed the Rhine on a pontoon bridge above Oppenheim on March 24, then reverted back to supporting the 4th Armored Division on their swift advance east to encircle the city of Frankfort. Within days they advanced across northern Bavaria, heading northeast. On April 3 they ended a long road march near the city of Gotha with enemy aircraft and artillery firing on their advance. After an ultimatum Gotha surrendered the next day and the 276th moved south on the road to Ohrdruf.

On April 5th the battalion fired on the city of Ohrdruf against stubborn resistance by the Germans. When the enemy surrendered, the Americans learned why they defended it so stubbornly. Ohrdruf was a sub-camp of Buchenwald – the concentration camp and ‘death factory’ – and the first such camp discovered by the Americans. Although my father-in-law never spoke of it directly, Patton visited the camp and ordered that as many of his men as possible tour the camp as witnesses to the atrocities committed there. More than likely the men of the 276th saw the camp at Ohrdruf and, possibly Buchenwald, since they were in the area when it was discovered. The only time I ever heard my father-in-law say anything about the concentration camps was in the 1990’s when a TV program mentioned that there were people claiming the holocaust never happened. He adamantly insisted that it did happen, but he would say no more.

Reassigned to the 11th Armored Division, the 276th drove southeast from near Suhl to near Kulmbach by April 12, battling not only Germans but also heavy rains. As part of Task Force Hearn another road march began near Grafenwohr, “site of the largest barracks and training area in central Germany,” and within a week they traveled 150 miles to Grafenau. Their objective was Linz, Austria on the Danube. The German army offered little resistance during this advance.

But, on April 30, the enemy made a stand at Wegscheld. After an all day assault, including heavy fire from the 276th, the 11th Armored Division occupied the demolished town. The battalion fired approximately 1,600 rounds that day, including a 90 round white phosphorous concentration. May 1st the 276 crossed into Austria with the 11th.

On May 2, the 276th received orders to return to supporting the 4th Armored Division near Lalling, Germany. They marched back to the northwest, then on May 3 moved to a ‘rest’ bivouac area near Saldenberg for three days. On the 5th they joined the 4th Armored Division moving east and north into Czechoslovakia toward the city of Strakonice. The Czech’s lined the roads welcoming their liberators. They were still moving toward Prague when they received word that the German armed forces had surrendered. The war in Europe was over.

Surrendering German troops streamed through the battalion’s camp toward designated assembly areas. On May 10 the 276th motored to Bogen, Germany, where they became part of the military government and oversaw the flow of prisoners into fenced areas for processing to prisoner of war camps.

The joy and relief of victory in Europe was short-lived for the 276th. On May 13 they learned they would be deployed within 30 days to the Pacific Theater, traveling through the United States. On May 16 they participated in a ‘ceremony shoot’ for a group of Russian generals. On June 2 they received orders to move out. The heavy vehicle column traveled across Germany and France by train while the light motor column traveled by road meeting up at Camp Lucky Strike, near Le Havre, France. Here, due to the points system for discharge, members of the battalion with more than 85 points were transferred to the 341st FA Battalion of the 89th Infantry for transport home and discharge.

The remainder of the 276th embarked for the US from Le Havre, France, on July 2, 1945. It was one year to the day from their departure from New York. By July 11 all had departed Camp Shanks, NY, for home on furloughs. Thankfully, by the time they were to reassemble for redeployment training, the Japanese had surrendered and the war was over.